REKOOBE APT-31 Linux Backdoor Analysis

[rekoobe apt backdoor ioc pcap network linux elf ltrace radare2 In this post I will be taking a look at a Linux backdoor known as REKOOBE1

Reporting suggests this and previous iterations have been used by APT-31 against a variety of victims.

This post will go over both static and dynamic analysis techniques, as well as provide some primitive scripts to automate extracting the C2 details.

The sample for this analysis can be found here and here with the SHA1: 23e0c1854c1a90e94cd1c427c201ecf879b2fa78.

As with previous posts, it might be beneficial to follow along, and hopefully the post is structured in a way that makes that possible.

Output from commands and scripts used for this post can be found in this Github repository.

Static Analysis

The start of any analysis should be to verify what it is that needs analyzing.

Using the file2 command, the output shows the target file is a dynamically linked 64-bit ELF executable.

This is a hopeful start as any imported functions should be visible to us, unless the sample is packed.

file rekoobe.elf

rekoobe.elf: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked,

interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.18,

BuildID[sha1]=025ab2845d244964abc35fb2cffadf388408fa14, stripped

One additional take-away from the file output is the “GNU/Linux” version that is referenced: 2.6.18.

Whilst compiling code on modern compilers will generally result in older versions being targeted for compatibility reasons, this version is well beyond expected values.

There are at least two reasons for this:

1) The binary was compiled on a very old Linux system.

2) The binary is designed to be deployed on potentially very old Linux systems.

For reference, version 2.6.10 of the Linux kernel was released in 20063

The output of the strings command also hints this sample was compiled using a version of GCC from 20124.

strings rekoobe.elf

...

GCC: (GNU) 4.4.7 20120313 (Red Hat 4.4.7-4)

...

Before wading into the depths of functions, reviewing the required shared libraries shows that anything imported is pretty standard. No additional functionality in custom shared libraries as is sometimes the case with Windows malware.

readelf -d rekoobe.elf

Dynamic section at offset 0x14028 contains 23 entries:

Tag Type Name/Value

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libutil.so.1]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [librt.so.1]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libpthread.so.0]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libc.so.6]

...

I have radare25 installed so will be making use of various tools from the framework. You do not have to use the same tools, any tools for interrogating ELF files should work fine.

Using rabin2 to list the imports, shows that this sample makes use of the execv function, which allows execution of arbitrary system commands.

The output below is truncated, the full output can be viewed here.

In addition to execv, the output also showed execl, recv, setsockopt, bind, and openpty, which all seem a little suspicious. These functions resemble the basis for a backdoor, and certainly should raise some eyebrows.

rabin2 -i rekoobe.elf

[Imports]

nth vaddr bind type lib name

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

1 0x00401790 GLOBAL FUNC daemon

2 0x004017a0 GLOBAL FUNC chmod

3 0x004017b0 GLOBAL FUNC dup2

4 0x004017c0 GLOBAL FUNC execv

5 0x004017d0 GLOBAL FUNC memset

6 0x004017e0 GLOBAL FUNC setsid

7 0x004017f0 GLOBAL FUNC shutdown

...

You shouldn’t take my word for it either!

Rather than going through every imported function and reading the documentation, Capa6 provides a nice way to scan for functionality of binaries.

./capa ./rekoobe.elf

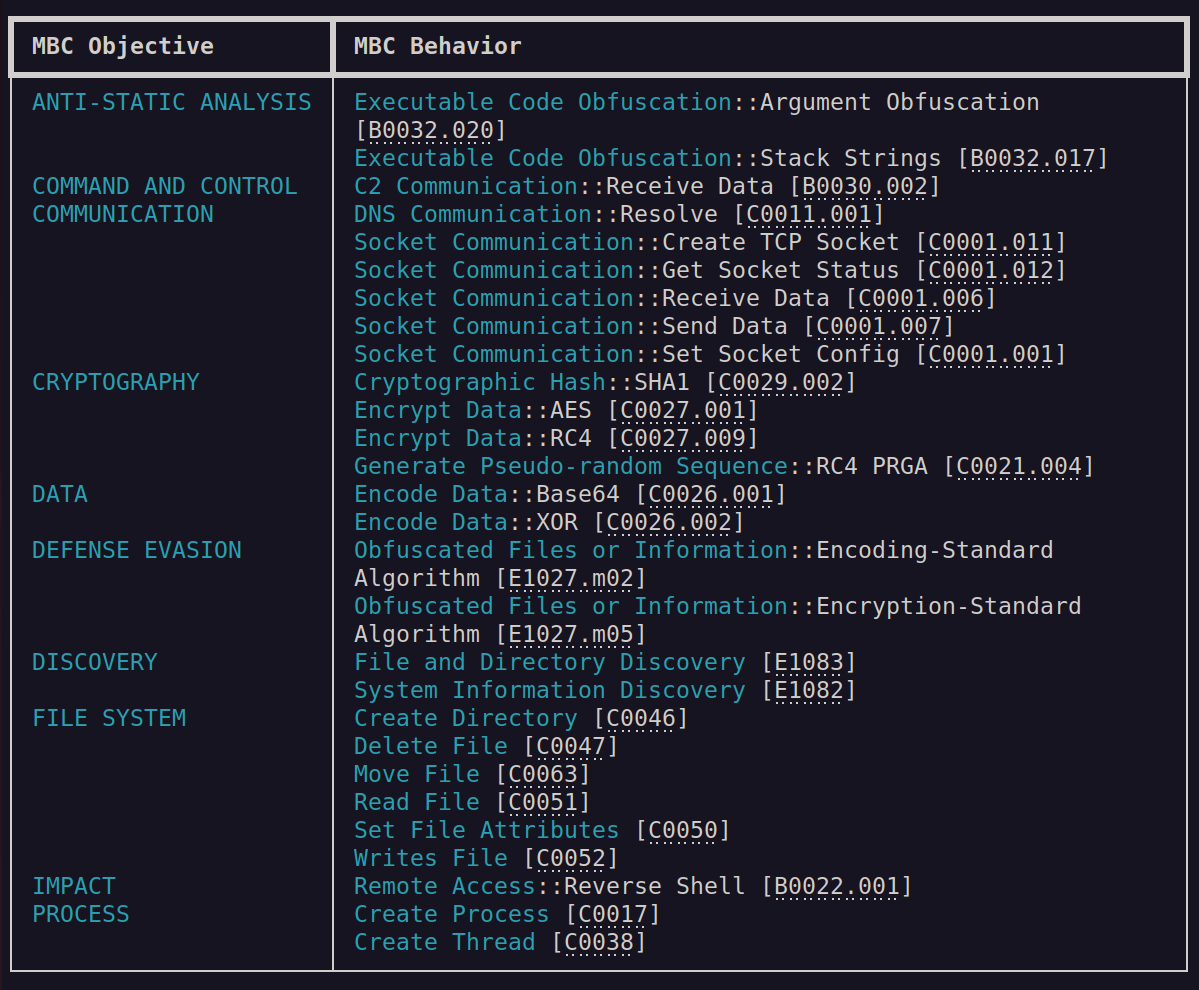

Figure 1: Capa output for Rekoobe sample.

The output in Figure 1 shows Remote Access::Reverse Shell, which pretty much sums it up, case closed.

The Capa output shows that there are references to RC4 and AES encryption routines, which might be interesting to take a look into. The full output from Capa can be found here.

Let’s start exploring the binary in a disassembler.

The main symbol is exported so should be quickly identifiable in other tools such as Ghidra7 or IDA.

The following command will print dissasembly located at the main function.

r2 -AA -q -c 'pdf @ main;' rekoobe.elf

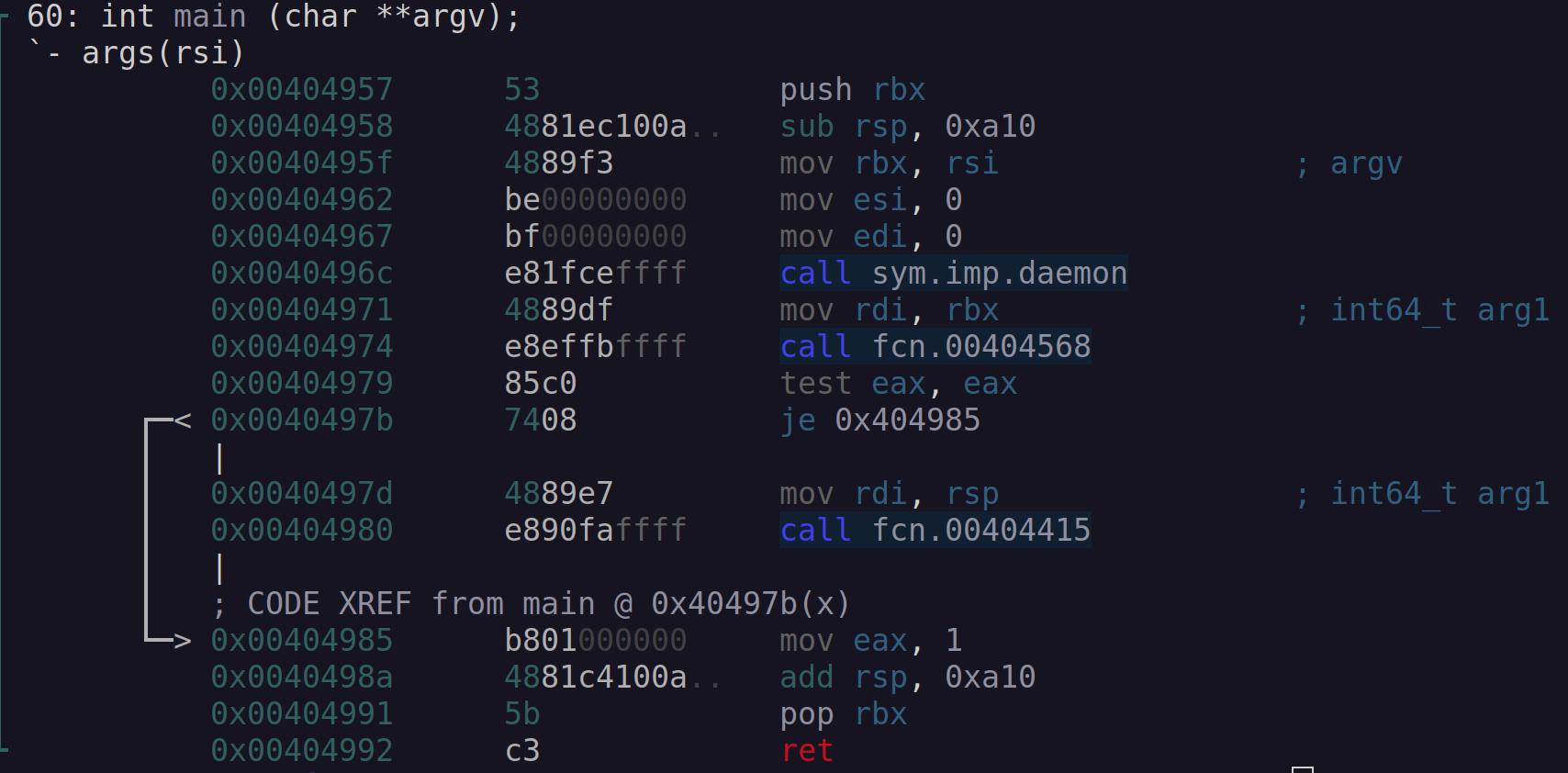

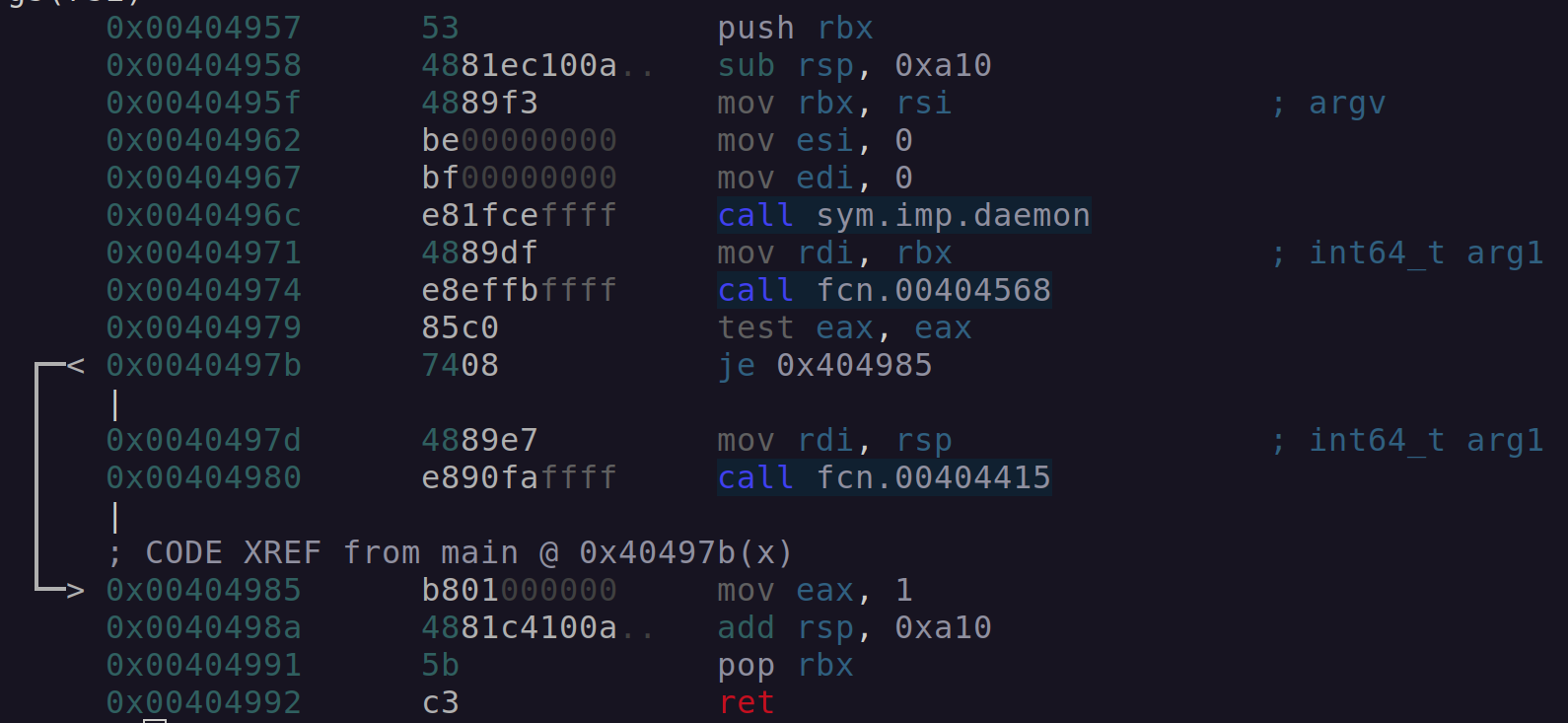

Figure 2: Radare2 main routine.

The output shows that the process first calls the imported symbol daemon, allowing the execution to continue in the background. A function labeled fcn.00404568 is called, and the return value in EAX is checked before calling another function labeled fcn.00404415.

Static Analysis: fcn.00404568

Starting with fcn.00404568 the command below prints the first 27 instructions of the function.

Why 27? Because it looked nice in the screen shot.

r2 -AA -q -c 'pd 27 @ fcn.00404568' rekoobe.elf

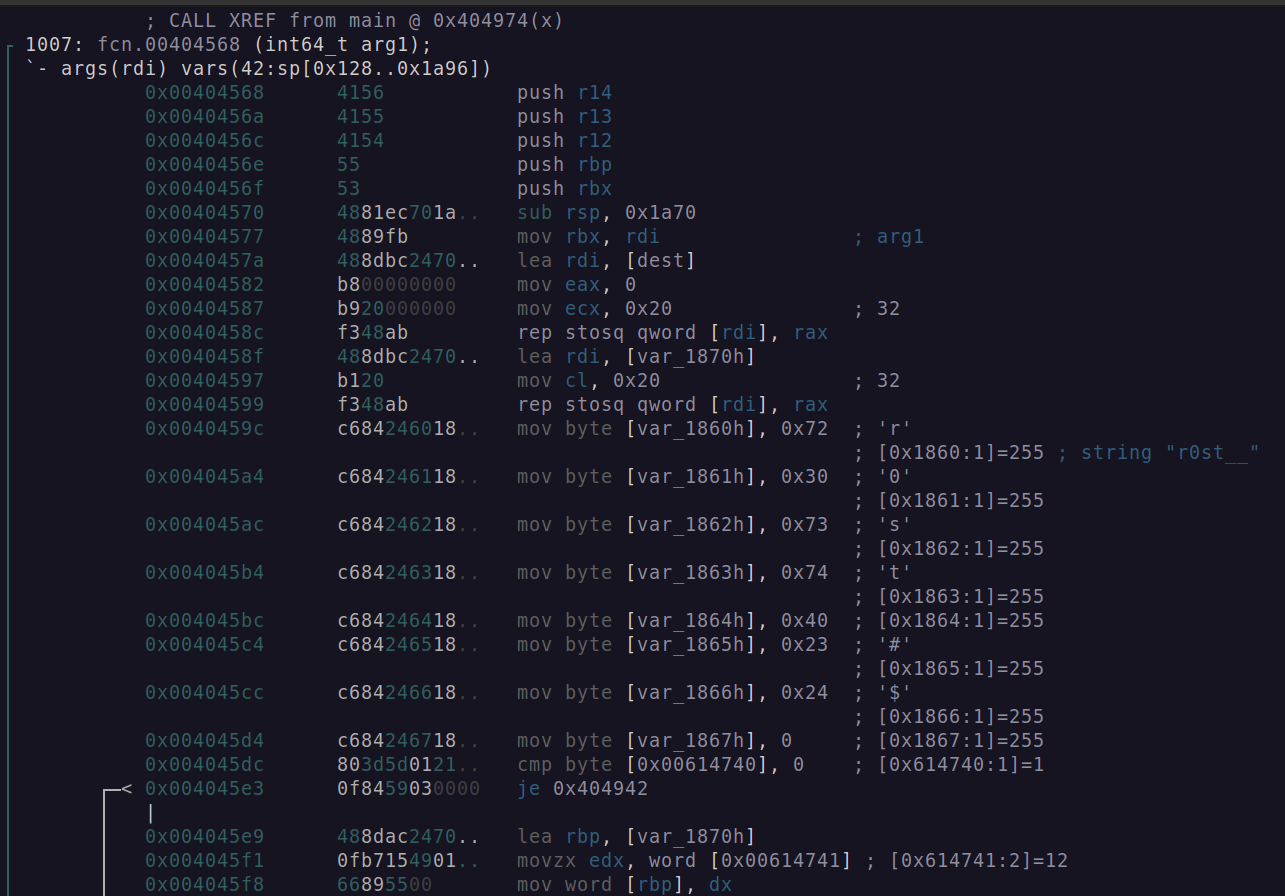

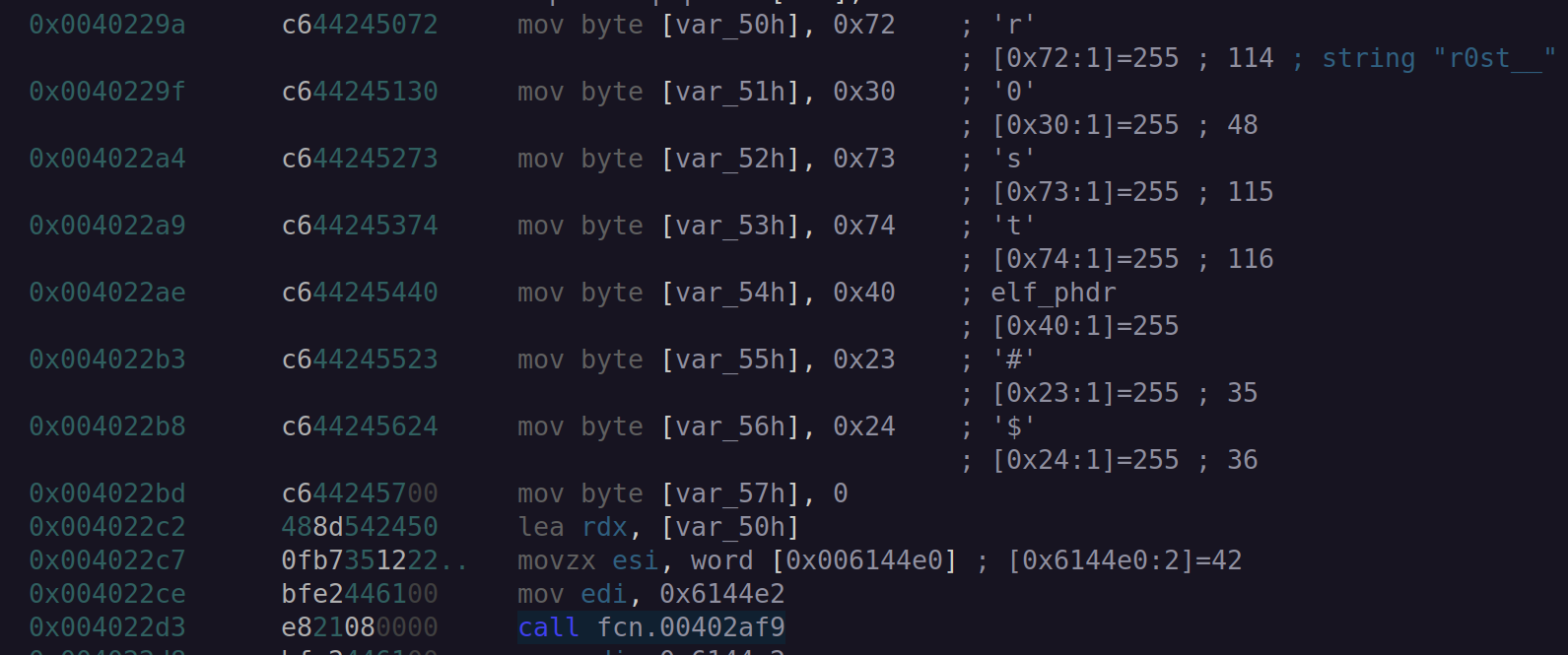

Figure 3: Radare2 fcn.00404568 disassembly.

Starting at 0x0040459c, there is a sequence of 8 mov byte instructions.

The 8 bytes are ASCII characters depicted as shown:

The \0 (NULL) byte terminates the character array.

0x72 = r

0x30 = 0

0x73 = s

0x74 = t

0x40 = @

0x23 = #

0x24 = $

0x00 = '\0'

Following the mov byte instructions there is then a value comparison with a byte located at 0x00614740 located in the .data section of the ELF file.

If the value is set to 0, then the je, jumps to the end of the function before returning.

This value turns out to be quite important later on…

The Capa output told us there was stack strings in use, and this is one of them. At this stage it is not important what this string is used for, however if there are more, it would be nice to recover them.

I created a script to recover these strings, which you can view here The output shown is truncated. A copy of the full output can be viewed here

python3 ./recover_stack_strings.py ./rekoobe.elf

%02x

%02X

r0st@#$

/etc//etc/issue.net

/etc/issue

/proc/ve/etc/issue.net

/etc/issue

/proc/version

r.

/

.

/

%s/%s

.

..

rb

a+b

a+b

/usr/usr/include/sdfwex.h

/tmp/.l

...

Whilst the output is far from perfect and not production ready, you can see it located the r0st@#$ string correctly, as well as some interesting file paths.

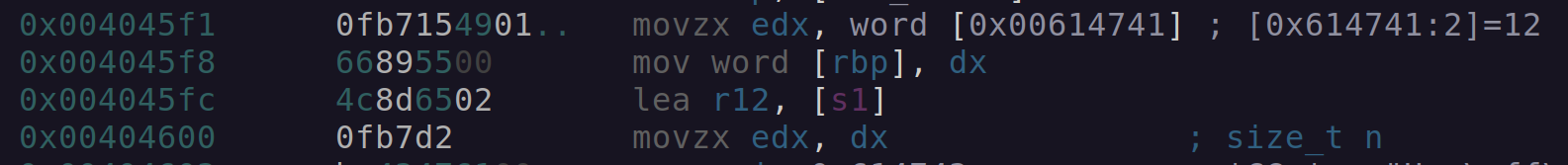

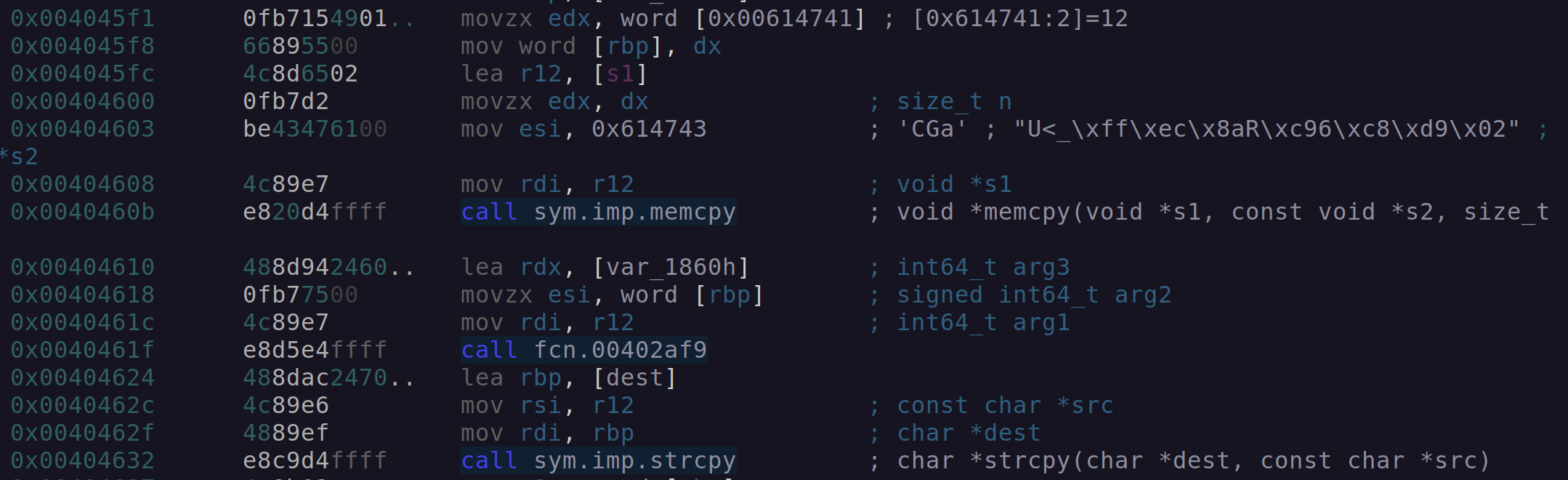

Continuing on, a WORD (2 bytes) is read from 0x00614741 into EDX with the value of 12.

Figure 4: Radare2 size parameter read.

Zooming out, shows the use of this parameter more clearly.

A memory address 0x614743 is stored into ESI, before both are passed into memcpy, to copy 12 bytes from the location stored in ESI into a buffer labeled s1.

After the memcpy function returns the stack string we recovered earlier located at [var_1860h], the value 12 and the address of the s1 buffer as passed to a function called fcn.00402af9.

Figure 5: Radare2 string operations.

Static Analysis: fcn.00402af9

The functionality of fcn.00402af9 is an implementation of the RC48 cipher.

The parameters passed to fcn.00402af9, are shown in the function prototype.

void fcn.00402af9(

char *buffer,

int64_t length,

char *key

)

The buffer contains the ciphered data on input, and on output contains the original clear-text data.

The length contains the length of the data stored in the buffer, as \0 (NULL) bytes will not be used to terminate the data.

Finally, the key, in this call is the r0st@#$ string.

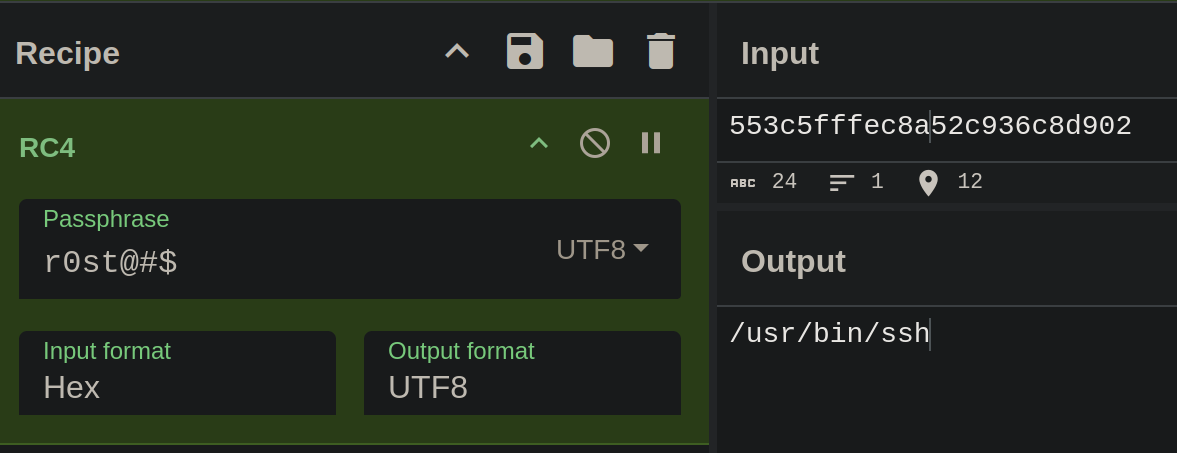

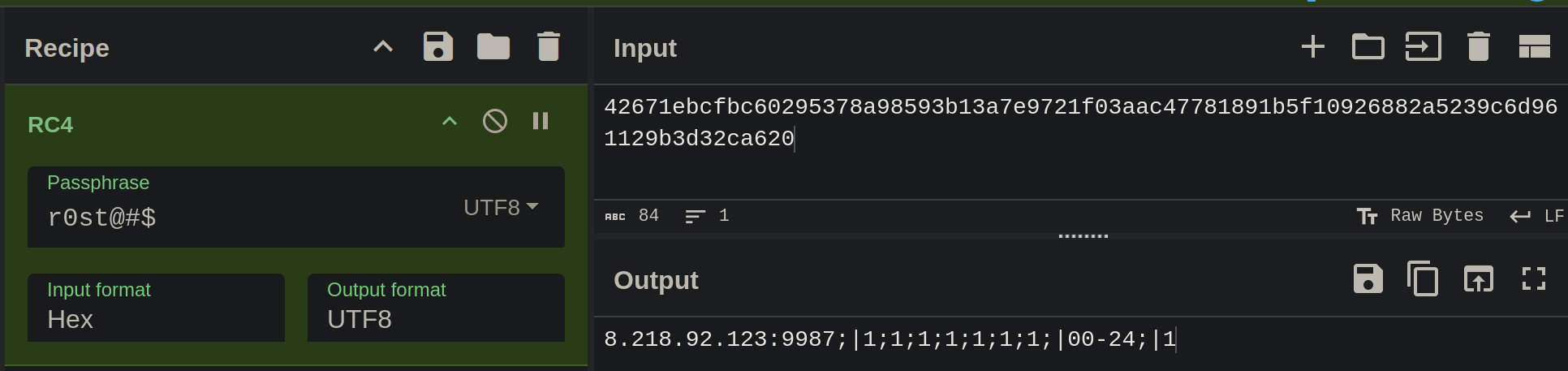

We can quickly test this out taking the various inputs and using the RC4 CyberChef recipe.

First extract the 12 input bytes from 0x614743.

r2 -AA -q -c 'px0 12 @ 0x614743' rekoobe.elf

553c5fffec8a52c936c8d902

Figure 6: CyberChef RC4

As the RC4 code was its own function, we can find cross-references to this routine to locate more values being decrypted that might be useful in later analysis.

The axt command shows there are 10 calls to this RC4 function, which are worthy of further exploration.

r2 -AA -q -c 'axt @ 0x00402af9;' rekoobe.elf

fcn.0040225c 0x4022d3 [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.00404568 0x40461f [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.00404b27 0x404dc8 [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.00404b27 0x404ea4 [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.00404f06 0x405130 [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.00404f06 0x40525d [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.0040ba91 0x40bad4 [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.0040ba91 0x40bb10 [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.0040bbe3 0x40bc5e [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

fcn.0040bbe3 0x40bcf2 [CALL:--x] call fcn.00402af9

Static Analysis: fcn.00404568 (continued)

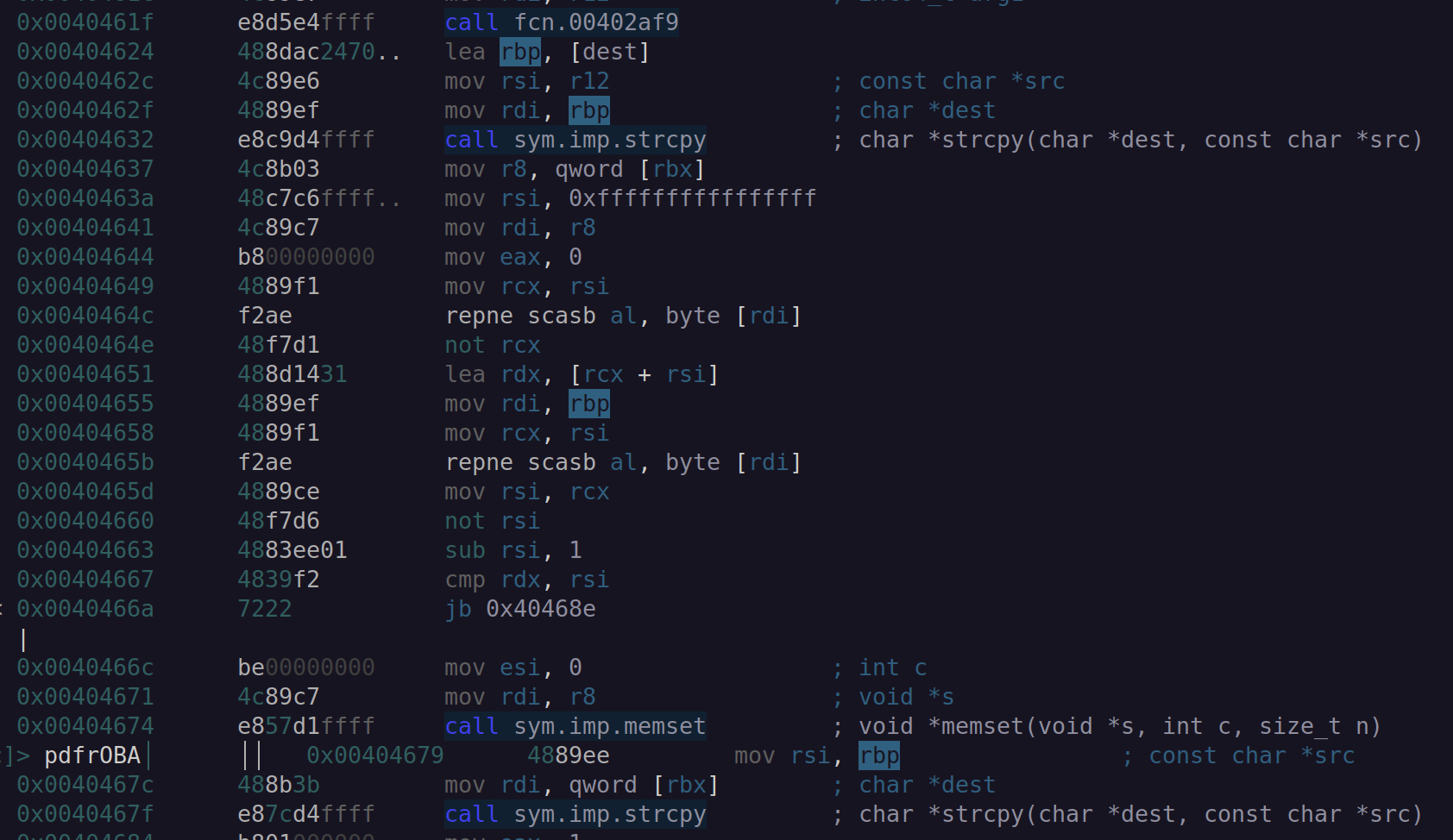

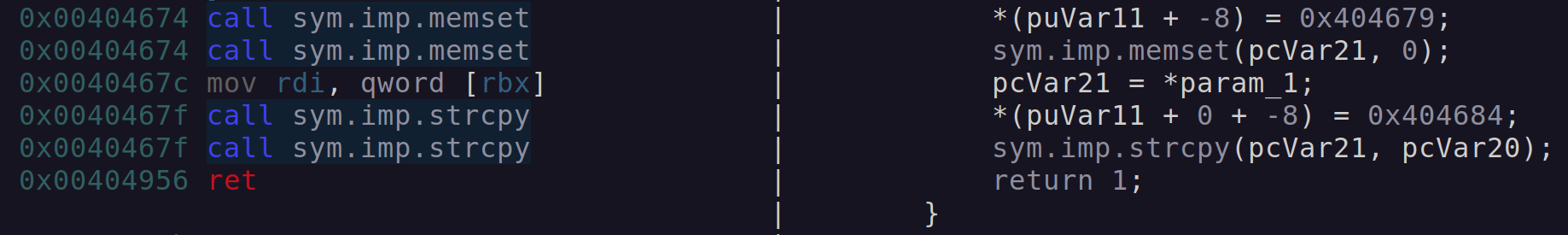

Returning (pun intended) back to fcn.00404568, we now have a decrypted string:

/usr/bin/ssh

Figure 6 shows a call to strcpy (0x0040467f), which shows the value stored in RBP moved into RSI as the source of the string copy operation. The screen shot shows that RBP contains the buffer address used to decrypt the string using the RC4 decryption routine.

Figure 6: Radare2 string operations.

Using the Ghidra plugin9 for Radare2 with the command pdga, Figure 7 shows the destination more clearly, as *param_1.

Figure 7: Radare2 Ghidra disassemble .

Going back to see what was passed into this function shown in Figure 8, we see from main that argv is the only parameter supplied (0x00404971).

Figure 8: Radare2 call fcn.00404568 .

Overwriting argv will for all intents and purposes alter the process name, allowing the process to avoid detection. When executed, this process will appear to be named /usr/bin/ssh, when commands such as ps and top are used to inspect the system.

This function contains more capabilities to copy and rename itself based on the value that is checked, however in this sample, it returns to main setting the return code to 1 which allows execution to continue into fcn.00404415 shown in Figure 8.

Static Analysis: fcn.0040225c

From the main function, fcn.00404415 is called which performs some value checks before calling fcn.0040225c.

The start of the function builds the same stack string r0st@#$ as previously seen, and calls the same RC4 wrapper. The input length is stored at 0x6144e0 and contains decimal 42.

The 42 bytes of input is located at 0x6144e2, again in the .data section.

Figure 9: Radare2 decrypt configuration.

The following command will extract the hexadecimal stream to be decrypted.

r2 -AA -q -c 'px0 42 @ 0x6144e2' rekoobe.elf

42671ebcfbc60295378a98593b13a7e9721f03aac47781891b5f10926882a5239c6d961129b3d32ca620

Using the same CyberChef recipe as before, it shows an IPv4 address and port, as well as some binary flag values.

Figure 10: CyberChef decrypt configuration.

There are 4 sections in this configuration, delimited by | values.

These sections are identified using the strstr function by the malware.

Configurations options are then further split using ;, before being parsed using strtol to convert the string values “1” to a long integer.

Static Analysis: fcn.00401db4

Before heading into some dynamic analysis, I thought it was worth highlighting the function fcn.00401db4.

The script to recover the stack strings highlighted some interesting file paths common on Linux systems. This function is where they reside and it responsible for collecting information regarding the infected system.

The stack strings, reveal the following file paths:

/etc/issue.net/etc/issue/proc/version

First /etc/issue.net is passed to fopen and if that fails then /etc/issue is opened.

The procfs file /proc/version is opened and strstr us used to locate the value x86_64, which determines the host architecture.

A call to gethostname is fairly self explanatory, gathering the hostname.

A call to getifaddrs returns a structure containing a linked-list, which is traversed gathering the IP address from each network interface.

Dynamic Analysis

From the static analysis, the command and control IPv4 was determined. Unfortunately at the time of analysis no response on the provided port was returned.

To see how the sample would have interacted with the server, we need to provide a route to the IP address: 8.218.92[.]123.

This can be achieved using the lo loopback interface as shown.

sudo ip addr add 8.218.92[.]123 dev lo

Once the IP address has been added, a nc netcat listener can be setup on the required port.

nc -l -p 9987 > output.bin

Using the ltrace10 program, it is possible to trace the library calls of this dynamically linked executable, saving the output into the ltrace.out file. A copy of the full output can be found here

ltrace -fbS -o ltrace.out ./rekoobe.elf

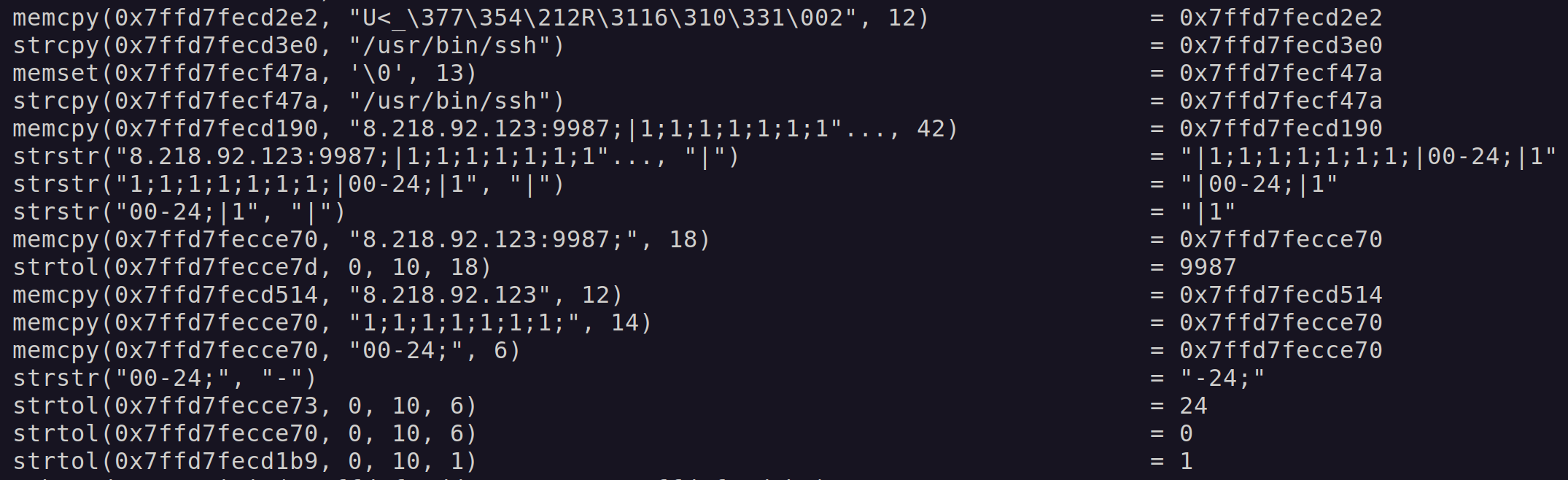

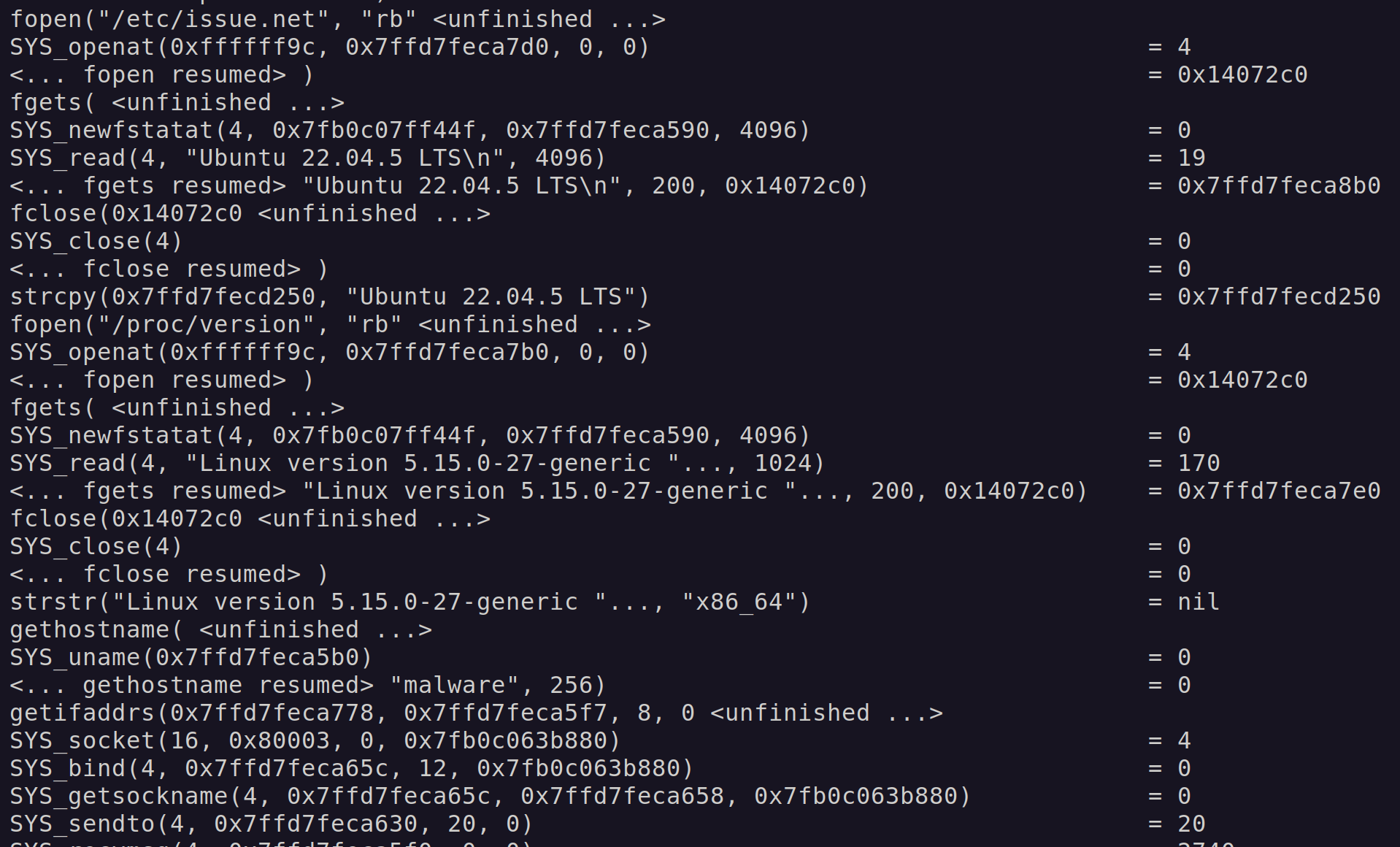

Figure 11 shows the output of ltrace revealing the configuration strings.

Figure 11: ltrace decrypt configuration.

Figure 12 shows the various files being opened to gather information regarding the host.

It also shows a call to the socket and bind functions, indicating a listing port being established.

Figure 12: ltrace decrypt configuration.

The dynamic analysis confirms the findings from the static analysis.

In a slightly modified lab setup, I was able to capture the network communications between the malware and the C2 server.

The PCAP file is available here, and shows that 548 bytes were sent over the TCP socket. The data in both directions is binary data, rather than encapsulated in HTTP.

Configuration Extraction

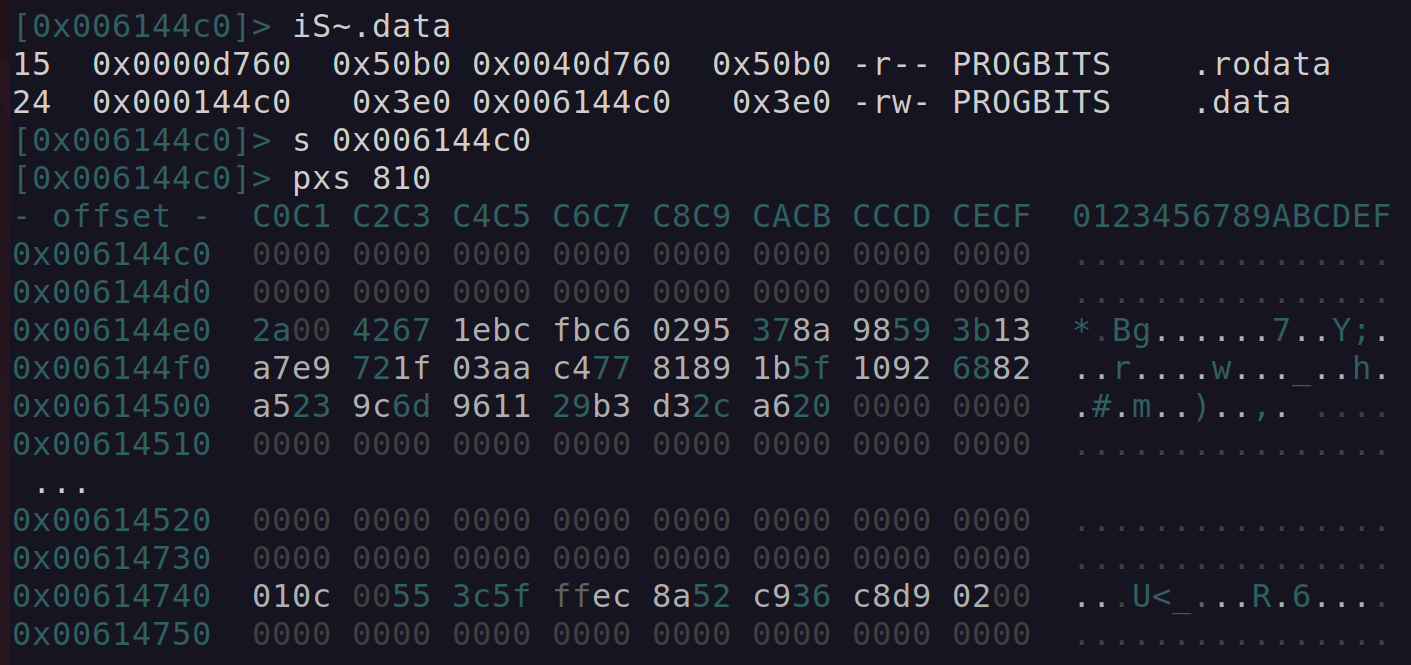

From the analysis performed, both the process name and configuration string were stored in the .data section.

Using radare2, locating the .data virtual address, and printing the hexdump shows the encrypted strings.

iS~.data

s 0x006144c0

pxs 810

Figure 13: Radare2 .data section hex dump.

Using this information, I have developed a configuration extractor which can be found here

Executing the script, and providing the RC4 key outputs JSON document containing the C2 details.

python3 ./rekoobe_config.py rekoobe.elf r0st@#$

{

"c2": "8.218.92.123:9987",

"flags": {

"unknown_0": 1,

"unknown_1": 1,

"unknown_2": 1,

"unknown_3": 1,

"unknown_4": 1,

"unknown_5": 1,

"unknown_6": 1

},

"hours": "00-24",

"process_change": 1,

"process_name": "/usr/bin/ssh",

"unknown": 1

}

Conclusion

In this post we have explored the initial workings of the REKOOBE backdoor, identifying how the command and control details are retrieved and shown a Python script to extract the details.

There is more to this sample, however the internals of this backdoor have been researched in prior work. Some notable research from AhnLab and hunt.io among others.

If you enjoyed reading or learnt something new, let me know!

You can find me on Twitter (currently known as X) as well as BlueSky.

Until next time, keep evolving.